Based in London, Sam Atis is a writer interested in Effective Altruism. He was awarded an Emergent Ventures grant for his writing (Samstack) and previously worked as a researcher at the Social Change Lab. Currently, he is applying for PhDs in Political Science and hopes to study how personality psychology interacts with political preferences.

Have you ever heard of a Perkins Tractor? If you lived in London in the 18th Century, you could buy a pair of Perkins Tractors (shown above) for the steep price of five guineas, and wave them over an aching part of your body for about twenty minutes as a way of relieving your pain. They worked, sort of. People who bought and used Perkins Tractors really did report feeling that their pain had gone away, even though there was no physiological reason they should work. John Haygarth, a British doctor, was intrigued. He organised a trial at a British hospital with several patients who were treated with fake Perkins Tractors - instead of being made of the expensive metal alloys, they were made with cheap wood. They worked just as well as the Perkins Tractors that were selling in London street stalls for five guineas, and thus the Placebo effect was demonstrated for the first time - “Such is the wonderful force of imagination!”, remarked Haygarth.

Wooden Rods aren’t often used as placebos these days, you’re much more likely to receive some kind of oral placebo (like sugar pills), a topical placebo (such as a cream containing no active ingredients), or an intra-articular placebo (injected directly into the joints). However, this presents a tricky dilemma - what do we do about the fact that different types of placebo can have different effect sizes? Here’s one study that’s interesting - researchers from Tufts Medical Center looked into how patients with osteoarthritis react differently depending on which type of Placebo they receive. An intra-articular placebo is more effective at relieving pain than topical placebos, and topical placebos are more effective than oral placebos. This is perhaps fairly intuitive - my impression is that, in some sense, I take an injection more seriously than I do taking a pill. What is interesting is that the difference in effect size between an intra-articular placebo and an oral placebo is sometimes larger than the difference in effect size between active pain relief drugs and oral placebo. The difference in effect size between an intra-articular placebo and an oral placebo is 0.29 (CrI 0.09 to 0.49), whereas the difference in effect size between acetaminophen (paracetamol) and an oral placebo is only 0.18 (CrI 0.05 to 0.30).

But the type of placebo used isn’t the only thing that can affect how effective it is - characteristics of the physician administering the placebo can also make a difference. In this study, doctors injected histamine into patients to induce an allergic response, and then gave patients a placebo cream. Patients were either told that the cream would alleviate the response (positive expectations) or that it would exacerbate the response (negative expectations). The doctors administering the placebo changed how warm/cold they were to patients, as well as how competent/incompetent they came across. To appear warm, doctors called patients by their names, made more eye contact, and so on. To appear more competent, they made no mistakes in the procedure (as opposed to those appearing incompetent, who put the blood pressure cuff on incorrectly), made sure the room was tidy, etc. Patients perceived these differences - they rated the doctors attempting to appear warm as more warm, and they rated the doctors attempting to appear competent as more competent. The result can be seen in the chart above - there is an interaction effect between expectations and doctor warmth/competence on the size of the allergic reaction - among patients who were told the cream would alleviate their allergic response, the warmth/competence of the doctor made a difference to their allergic response, whereas among patients with negative expectations, the doctor characteristics made no difference.

Characteristics of the patient can also make a difference to how effective a placebo is - children are more receptive than adults (study can be found here). The study here gestures at a problem that all of these findings may lead to: in RCTs comparing how responsive adults and children were to anti-epileptic drugs, the treatment effect was significantly lower in children. The reason for this was not actually that the drugs were any less effective in children, but that because children were more receptive to the placebo, the active drug looked less effective in comparison.

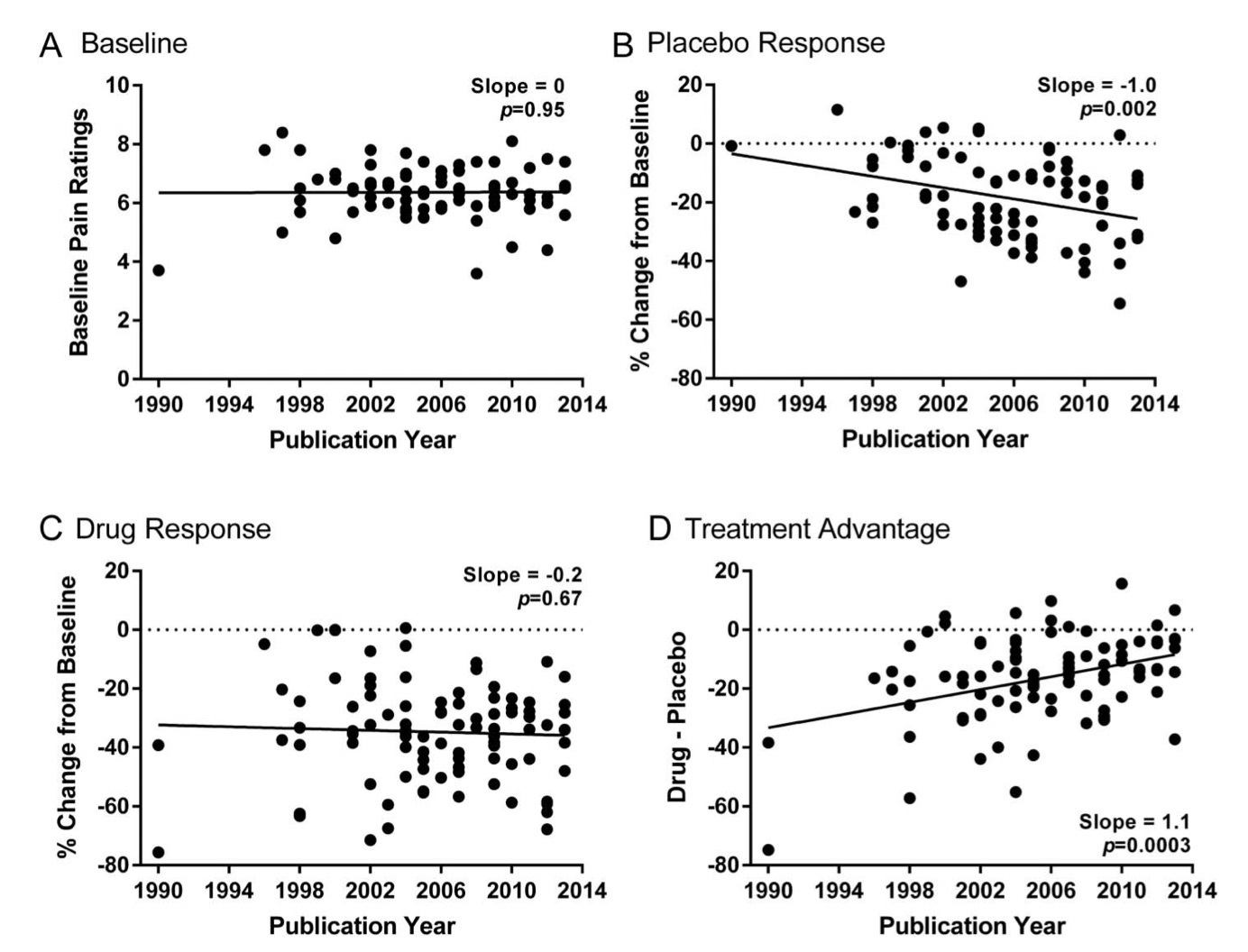

The implications of this are pretty serious - the placebo effect in the United States has actually become quite a lot stronger over time, meaning that drugs that once would have been approved may not be now - because their performance relative to that of placebo is less convincing. This study makes the point clearly - by 2013, drugs produced 8.9% more pain relief than placebos, compared to 27.3% in 1996. In the charts above, it can be seen that the effect of placebo drugs has increased a lot, whereas the effectiveness of pain relief drugs has barely changed, meaning that the treatment advantage (the effectiveness of active drugs as opposed to placebos) has fallen dramatically. Weirdly, it seems like this is only happening in the United States, whereas other countries haven’t seen particularly large increases in the effect size of placebos.

Maybe I just hadn’t thought about the Placebo effect enough, but I hadn’t really considered that the size of the effect could be so different depending on whether the patient was taking a pill as opposed to using a cream, the characteristics of the doctor, and so on. The obvious result of this is that certain medications appear less effective than they would do had a different type of placebo been used (or had the physician administering the placebo behaved differently, or had the patient been older/younger, etc.) - given that, over the past ten years, 90% of potential drugs for the treatment of cancer pain have failed at advanced stages of clinical trials, this seems like it’s worth thinking about a bit more.

Interesting article.

What I wish conventional medicine would come to see and embrace is that the mechanism of placebo is in effect 100% of the time, which is to say that regardless of the context, our beliefs - the neurological processes that interact with our cognitive perceptions - ALWAYS contribute to our health outcomes. Conventional medicine biases toward discoveries of innovative substances, but the bigger magic - by far - is the complex ability of a human body to create the chains of chemical events it needs to reach homeostasis. We should be harnessing that more. Many forms of alternative healthcare do.

Interesting that the placebo effect has gotten stronger over time. I wonder if that is because faith in science and medicine got stronger. If so, it would be interesting to see if there’s a drop-off after 2020 and the war on science.