Happy Thanksgiving to American readers! This is the first of two gratitude-themed posts by Dynomight (Previously: Underrated Reasons to be Thankful).

Dynomight writes about science and dispenses life advice at http://dynomight.net.

I was wrong about gratitude. I thought it was a guaranteed way to become happier and went around proclaiming we should be thankful because:

Hokey, unfashionable techniques like practicing gratitude turn out to have strong scientific evidence behind them.

Sorry about that. In my defense, the internet is rife with articles from seemingly credible places that say things like this:

Is it true that you can become healthier and happier by practicing gratitude? The short answer is yes.

And this:

Gratitude is strongly and consistently associated with greater happiness. Gratitude helps people feel more positive emotions, relish good experiences, improve their health, deal with adversity, and build strong relationships.

And this:

Even spending just a few minutes a day practicing gratitude can facilitate better sleep and lower blood pressure, according to research.

Who am I to argue with research, I thought? But of course, I hadn’t read the original papers. I recently did that, and… I think the scientific evidence for gratitude is mostly a mirage. It’s not just unsupported, it verges on disproven.

Now, this isn’t a criticism of the papers, which seem mostly OK. The problem is that things are being grossly misinterpreted and oversold in secondary sources. (Albeit, secondary sources that sometimes have loose quotes from the authors of the papers.)

This also isn’t to say that gratitude exercises don’t work. If you do them and you think they help you, that’s great and you should keep doing them. (And also… perhaps stop reading now?)

The problem with gratitude exercises is that everything works. In research, they’ve been compared to acts of kindness, visualizing your ideal self, keeping a mood diary, progressive muscle relaxation, and many other things. They all work. Even seemingly neutral things like listing your daily activities may work.

Why everything seems to work is a difficult question. But regardless of the answer, I think we have mistakenly fixated on the magical properties of gratitude when it’s really the magical properties of pretty much any damn positive-sounding activity you might make up.

Correlation

Claim: Gratitude is correlated with happiness.

Status: Strongly supported.

Gratitude and happiness are abstract concepts. For the above claim to mean anything, we need to talk about what measurements were taken. So let’s start with an early famous study.

McCullough et al. (2002) took some undergrads and measured their gratitude by having them rate a long list of statements like “I feel thankful for what I have received in life” or “I am grateful to a wide variety of people”.

Now, as every stoned philosophy major knows, there’s no one agreed definition of happiness. Instead, psychologists have many types of psychological well-being. This experiment tried to measure three of them:

Life satisfaction was measured through statements like “in most ways my life is close to my ideal”.

Subjective happiness was measured through statements like “I consider myself a very happy person”.

Vitality was measured through statements like “I have energy and spirit”.

Their results were that all of these different types of happiness were strongly correlated with gratitude (a correlation of around 0.5).

But that’s just one early study. How does it stand up twenty years later?

It holds up extremely well. Portocarrero et al. (2020) did a meta-analysis that included 144 different manuscripts including measurements from just over 100,000 total participants. Seven different types of psychological well-being all had correlations between 0.40 and 0.48. Six different types ofnegativewell-being had correlations from -0.27 to -0.42.

So the evidence that gratitude and happiness are correlated is pretty overwhelming. That’s interesting, but we’re interested in something else.

Causation

Claim: Gratitude causes happiness.

Status: Unclear.

Just because grateful people tend to be happier doesn’t mean that gratitude is making them happier.

As ever, correlation does not imply causation. And as ever, I cannot resist the urge to take a couple of shots at common practices in the social sciences. Papers acknowledge that correlation doesn’t imply causation, but rather than seeing this as a fundamental aspect of reality, there’s often this strange air of resentful exasperation. And when the researchers are talking to journalists outside of papers, they might switch back to causal language.

But we also have some specific reasons to doubt that gratitude is causing happiness. For one, gratitude is deeply interrelated with other personality traits.

The most common and “respectable” way of measuring personality is the Big Five. (Psychologists for whatever reason do not like Myers-Briggs.) Steel et al. (2008) did a meta-analysis of how the Big Five factors relate to happiness.

Big Five Factor Correlation with Happiness

Extraversion = 0.49

Agreeableness = 0.30

Conscientiousness = 0.25

Emotional stability = 0.46

Openness to experience = 0.13

We’ve talked about extraverted, agreeable, conscientious, emotionally stable people before. These “all-blues” seem to do better on basically everything from income to intelligence to loneliness to happiness.

How is the Big Five correlated with gratitude? You can probably guess: It’s positively correlated with all five of the above traits. This has been replicated many times (McCullough et al. 2002, 2004, Wood et al. 2009, 2010, Schueller et al. 2012, Szcześniak et al. 2020). The only paper that even partially disagreed was by Saucier et al. (1998).

So… Gratitude is correlated with happiness, the Big Five is correlated with happiness, and gratitude is correlated with the Big Five.

Why should we think that gratitude → happiness link is causal? The Big Five is more predictive of happiness than gratitude is—extraversion alone has a stronger correlation.

Wood et al. (2009) looked into this. They found that the Big Five alone could explain 53% of the variance in happiness (averaged over six different measures of well-being). But the Big Five plus gratitude could explain 55.67% of the variance.

You might conclude that gratitude doesn't tell you much once you know the Big Five. That is... not how Wood et al. see things:

Gratitude appears to provide some extra information, but not a lot. From this, it looks like gratitude is just another part of the big nexus of personality traits. There’s no obvious reason to single out gratitude as particularly important for happiness.

Causation?

Say you have a race car. You enter lots of races, but your car sucks so you always lose. One day you can’t take it anymore so you spend a ton of money on grippier tires and replacing the frame with lighter materials. And then you win.

Now I tell you, “The car’s increased agility caused you to win.”

At first, this seems fine. But the more you ponder it, the less sense this makes. There are many proposed definitions for what it means to say that “A causes B”. But the clearest interpretation is that “doing A results in B”. But “agility” is not a thing you do. It’s not even a property you can directly observe. If you want to talk about causality, you need to go back to how you improved your car.

Similarly, what does it mean to say that “gratitude causes happiness”. Does it mean anything?

Trait gratitude results from (I assume) life experience plus genetic factors. And then that gratitude influences behavior which influences life experiences:

Gratitude is not a lever an experimenter can pull. If we want to talk about causality, we should talk about…

Gratitude exercises

Claim: Gratitude exercises cause happiness.

Status: Depends on what you compare them to.

Again, to make sure we know what we’re talking about, let’s look at an early paper. Emmons and McCullough (2003) took some undergrads and assigned them to one of three conditions.

In the gratitude condition, students were supposed to think over the past week and list up to five things they were thankful for. Responses included “to the Lord for just another day” and “to the Rolling Stones”. In the hassles condition, students listed five hassles that occurred in the past week. (“Hard to find parking”) In the events condition, students just listed things that happened in the past week. (“Cleaned out my shoe closet”)

After doing the above, students rated how much they felt interested, distressed, excited, etc., which allowed researchers to estimate positive affect. After repeating all this for 10 weeks, here were the final effect sizes:

Effect on positive affect

Gratitude condition = 0.18

Hassles condition = -0.13

Events condition = -0.03

There was a small increase in the gratitude condition, a small decrease in the hassles condition, and little change in the events condition.

But that was 20 years ago. We’ve had many similar studies since then. What do they say?

Placebos

With any intervention, you need to worry about the placebo effect—changes that result not from the intervention, but from subjects’ expectations about the intervention.

With drugs, you can control this by giving the control group sugar pills. But with gratitude, you can’t divorce expectations from the treatment. So it’s critical to be clear about what’s happening in the control group.

One early review found that when you compared gratitude exercises to doing nothing, the effects were moderate. But when you compared it against any other activity, the effects halved. Oddly, this is despite many of the alternate activities being designed to be harmful, like listing hassles.

Dickens (2017) broke things down further. A negative control group did something seemingly harmful, like listing hassles or worries or misfortunes. A neutral control group did something neutral like listing events or did no activity at all. A positive control group did something seemingly good, like imaging your ideal self, performing an act of kindness, thinking positive thoughts, relaxation exercises, mindfulness exercises, deep breathing, or thinking about people less well-off than yourself. Here were the final effect sizes on a bunch of different outcomes:

Gratitude exercises look amazing when compared to negative interventions. But the benefits shrink greatly when compared to neutral interventions, and even further when compared to positive interventions.

Compared to other positive interventions, the only places where gratitude exercises much help are for grateful mood with an effect size of 0.23, and for positive affect with an effect size of 0.10.

How much is an effect size of 0.10? The standard classification puts it halfway between “small” and “very small”.

But I’d rather be concrete. Imagine a drug that made you taller. In the population of adult US men, an effect size of 0.10 corresponds to an increase of around 0.71 cm or 0.28 in. That’s not a lot, but if I wanted to be taller, I wouldn’t turn it down. And I wouldn’t turn down a similar effect on happiness.

But there’s another problem.

Replication

The replication crisis in psychology started in 2011 with the Bem affair. Since then, many previously accepted results have gone down in flames. This might be cause for skepticism, but my feeling is that gratitude interventions avoid many of the biggest sins. The idea that gratitude practice could increase happiness isn’t prima facie implausible. And it’s a pretty rigid hypothesis with uniform statistics, leaving less room for researchers to make up theories to fit their datasets. And, of course, there have been many replications.

But there’s another sin that’s particularly insidious. Say you do an experiment and get a boring result. You might decide to stop working on that topic, or reviewers might reject your paper. Because of this publication bias, experiments that happen to give interesting results are more likely to find their way into publications and meta-analyses, even with no obvious malfeasance.

The usual trick to deal with publication bias is to guess that it will be greater in papers with few subjects. With few subjects, the people who get high effect sizes will publish, while the people who get low effect sizes won’t’. Whereas, with high numbers of subjects, everyone should get nearly the same effect sizes.

(I also sometimes wonder if publication bias is weaker with larger samples for sociological reasons: If I spent millions of dollars running a trial, I’d fight very hard to see it published somewhere.)

There doesn’t seem to be any meta-analysis that looks at publication bias specifically for gratitude interventions. However, White et al. (2019) do one for many positive psychology interventions, including gratitude, well-being therapy, coaching, kindness interventions, and “fundamentals” (whatever that is).

Their title leaves little doubt about where they stand:

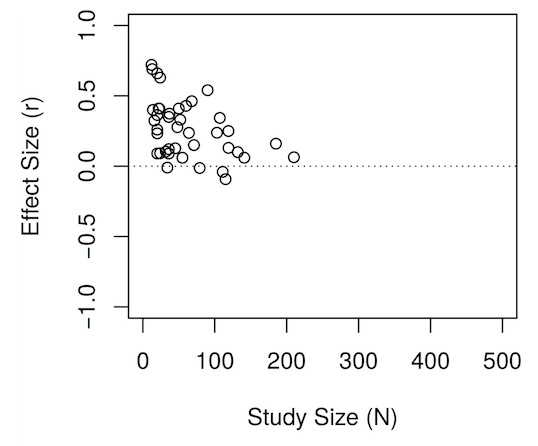

Here’s a plot they made for the effect sizes of different papers as a function of the study size:

The trend is pretty clear: Larger studies find smaller effects. And here’s a funnel plot:

In a funnel plot, each marker is a study. The ones with positive effects go to the right, while the ones with larger samples and less noise go to the top. If there were no publication bias, the markers should form a symmetric funnel. But above the points tilt strongly to the right at the bottom, suggesting significant publication bias. The curved grey line tries to account for this and suggests that controlling for publication bias should cut the mean effect size in half.

The above plots are an attempt to estimate the amount of publication bias in an earlier meta-analysis bySin and Lyubomirsky (2009). They do a similar analysis for an earlier meta-analysis byBolier et al. (2013)and find that adjusting for publication bias reduces the mean effect almost to zero.

Here’s the plot of study size vs effect size:

And here’s the funnel plot (correcting for publication bias drives the estimated effect almost to zero):

Again, this is looking at various positive interventions, not just gratitude. But you need a lot of studies to estimate publication bias, so this is probably our best bet for guessing the publication bias in gratitude exercises: We should reduce the effect sizes by between 50% and 100%.

Discussion

To summarize: Gratitude is correlated with happiness, but this doesn’t mean it’s causing happiness and it’s not clear if that statement even makes sense. When you look at gratitude exercises, they look good when compared to “negative” controls like listing all the ways your life is bad. But when compared to positive controls—basically anything that sounds good—the effects become pretty small. And our best information about publication bias says we should discount that number even further.

Now again, gratitude exercises probably do work! It’s just that there’s nothing special about them. My advice is: If you like gratitude exercises, keep doing them. But if you don’t like gratitude exercises, do something else. Anything. Just make up something that sounds good and do it. At the moment we can’t tell what details make a difference. You can debate if it’s all “placebo”, or if that question even makes sense, but I don’t think it matters in practice.

It’s sort of like different antidepressants or different types of therapy. They all weirdly seem to work about equally well on average, even though they have different mechanisms. But that doesn’t mean they will be equally effective for you.

And there’s another similarity: It’s debated if anti-depressants work better than placebo for mild depression, but they definitely work better than not doing anything. The notion of “placebo” is much more fraught with interventions like gratitude, but the lesson is still that you might as well do them.

But probably the biggest lesson is: Don’t sit around thinking about how bad your life is and how people have wronged you and how everything is unfair. Whatever the difference between gratitude and neutral activities might be, it’s much smaller than the difference between neutral activities and negative activities. So don’t do those.

FAQ

Does gratitude practice improve your physical health?

There is no evidence for this. Dickens et al. (2017) did a meta-analysis of this issue. Compared to negative controls (3 studies) or neutral controls (5 studies), gratitude exercises did almost nothing for physical health. Compared to positive controls (3 studies) gratitude had a small negative effect. But I wouldn’t take this too seriously, it’s probably just noise.

Does gratitude practice improve your sleep?

There is no evidence for this. Dickens et al. (2017) found that compared to both negative controls (3 studies) and positive controls (2 studies) gratitude had essentially no effect on sleep.

Does gratitude practice improve the quality of your relationships?

Unclear. Compared to neutral interventions (4 studies) Dickens et al. (2017) found quite a fairly large effect size of 0.51 on relationship quality. However, when compared to positive interventions (2 studies) the effect size was exactly zero.

Great job dealing with correlation versus causation and critically overviewing the literature on this topic. On personal level, I find gratitude to make me feel good but nothing beats giving :)