How we adapted to milk, and how we adapted it to us

Author: Saloni Dattani

Saloni Dattani is a researcher on global health at Our World in Data and a founder and editor at Works in Progress. This post and others like it can be found on her substack Scientific Discovery.

If you’re like me, you might have thought that digesting milk was a binary: either you were able to do it or you weren’t.

But that’s not true, and I only realised it when I discovered four years ago that I have partial lactose intolerance!1

And after reading much more into the topic, I found out about lots of interesting things about how humans adapted to digest milk, and how we adapted it to be digestible to us.

How we’ve adapted to milk

Milk is a great source of calories and nutrition, but it can be a major pain. Its sugar – lactose – is indigestible for many people around the world.

Newborns and infants produce an enzyme called lactase that can break down this sugar. But as they age, only some children and adults (who are called ‘lactase-persistent’) continue to produce it.

For others, the lack of lactase can mean drinking milk becomes intolerable, causing symptoms like constipation, bloating and diarrhoea.

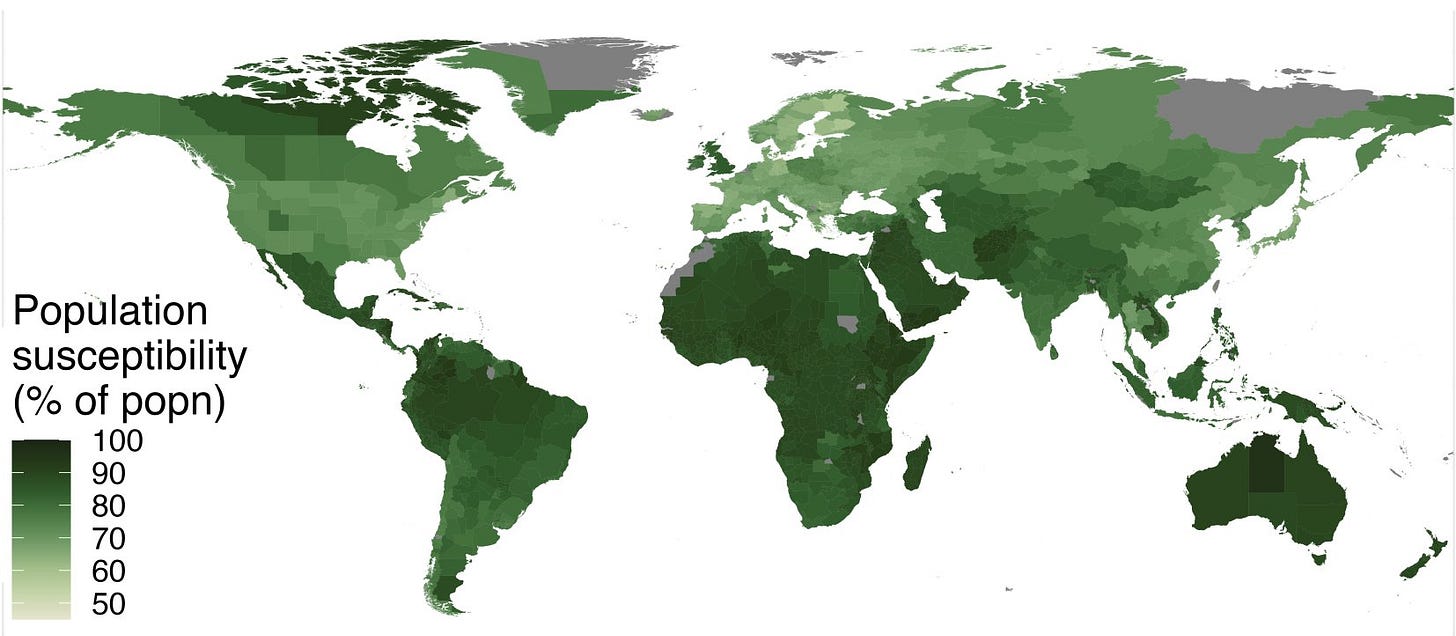

Today, the share of adults who produce lactase varies widely around the world, although we still lack good estimates of its frequency in many countries.

Lactose tolerance (being able to digest lactose) is common in Europe, South Asia and West and East Africa, while it seems to be much less common in East Asia, and Central and Southern Africa.

To see how it developed, let's first look at milk consumption in history.

It’s estimated that milk consumption became widespread in Europe from 7,000 BC onwards (shown below). Milk drinking grew as nomadic and pastoralist cultures migrated into the continent and spread the practice of dairy farming.

But the genetic mutations that allowed people to digest this milk only began to spread thousands of years later. You can see this in the maps below.

Across Europe, Asia and North Africa, lactase persistence is largely determined by a single genetic difference (13.910*T) near the LCT gene, which encodes the lactase enzyme.

This change in a single base of DNA, from a C to a T, quickly spread across Europe starting around 3,000 years ago. It means that most people in Europe today continue to produce lactase into adulthood.

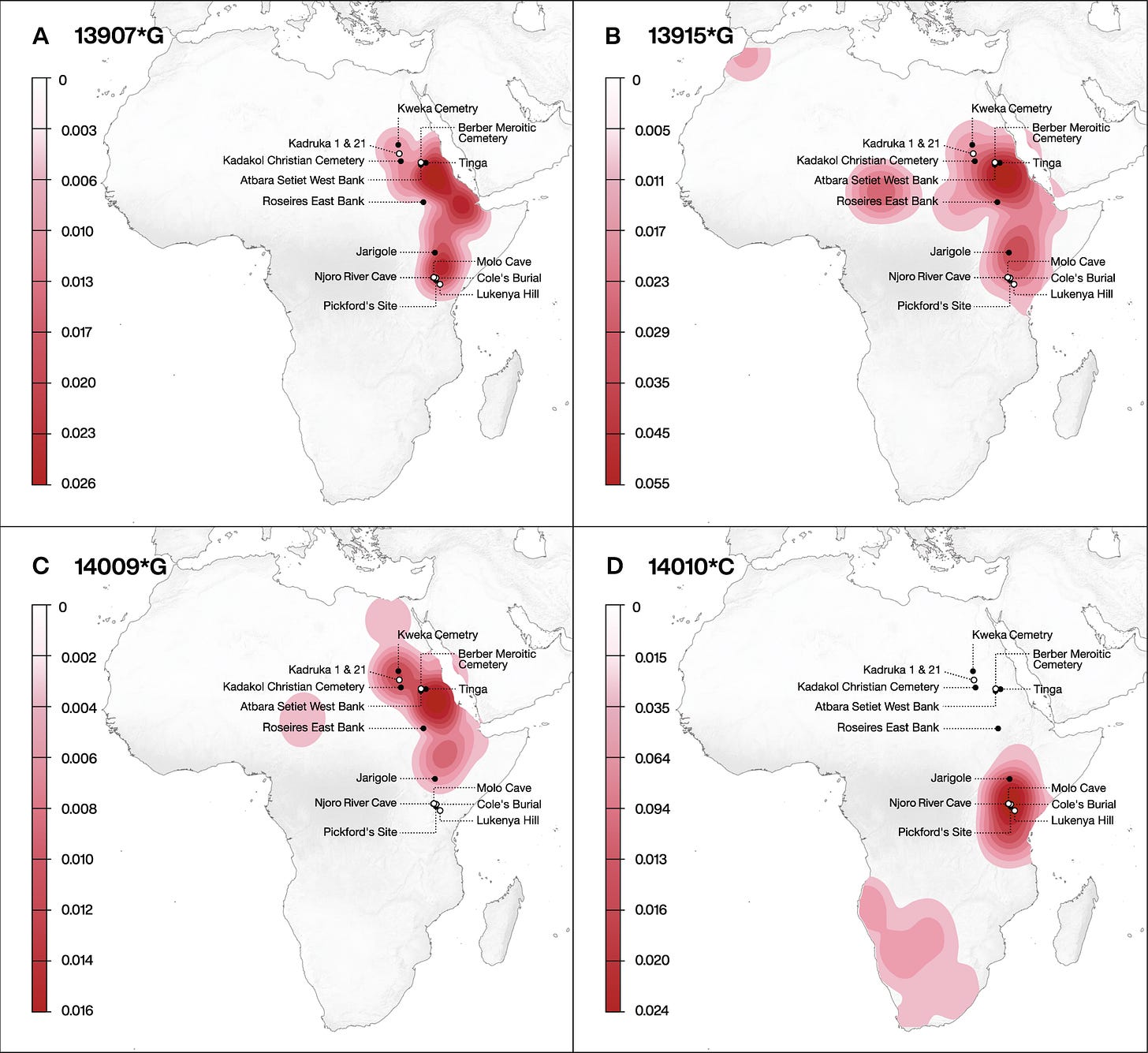

In the Middle East and East Africa, there are other genetic variants that help people continue to produce lactase. They also influence the same LCT gene, but are much less common. You can see them below.

But hold on a second. Why did it take thousands of years after people consumed dairy for the Eurasian lactase mutation to become common? How did people digest milk before that?

Part of the answer is that even without lactase, people can consume small quantities of milk without symptoms – by consuming it slowly or with the help of different intestinal microbes that are more efficient at breaking lactose down.

And milk from different animals contains different levels of lactose. Some types have low levels of lactose that wouldn’t have caused major problems.

But there are bigger reasons too.

Milk isn't the only source of food for people with lactose intolerance, of course. But when other sources of food were not available, due to drought or crop disease, the ability to digest it could have become pivotal.

People who farmed crops in sedentary cultures might suffer more in these situations. But people in pastoralist cultures, for example, might be able to migrate into other flourishing areas and rely on milk products from their herd. A major event like this might have given them a survival advantage and set off the spread of the genetic variant.

And there's more. Aside from these ways by which we adapted to drink milk, we also adapted milk to make it more digestible to us.

In many cultures, milk is commonly fermented into other dairy products, like yoghurt, kefir and cheese, for preservation. These have lower lactose content or contain microbes that help digest it.

It's really cool to think about how people in history developed fermentation techniques that made milk digestible when they didn’t have the enzymes to help them.

But today there are even better ways of doing it, because we can pin down the reason that milk indigestion develops.

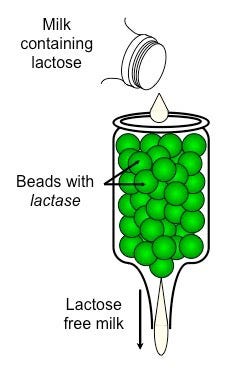

Thanks to the discoveries that lactose produced indigestion, that lactase broke it down, and that various microbes produced lactase too, we can now mass produce the lactase enzyme with moulds, yeast or bacteria.

Then, we can use it to process milk and turn it into lactose-free milk.2

Or we can just take lactase in a tablet with a meal, without changing what we drink or eat. That’s pretty neat!

So the ability to digest milk isn't a binary. It hasn't been a binary for a long time – because of cultural techniques to ferment milk – but it is even less so today, with the ability to mass produce the lactase enzyme.

And we also have lots of other milk sources and milk substitutes without lactose too – like coconut milk, almond milk, soy milk, and oat milk – which avoid animal suffering and the environmental impacts of dairy farming.

As someone who loves cheese, I think that's a great thing.

More links

Here’s some more great stuff I’ve been reading:

At Works in Progress, we’ve started a new Substack series of personal content from our authors. The first is by Stuart Ritchie on how science is usually done backwards, and his experience with turning it back around.

I’ve been looking for a study like this for months. Vaccination against smallpox ended in most of the world in the 1970s; since those vaccines also protect against monkeypox, some people alive today already have some immunity to it. This great paper estimates of how much protection each country already has against monkeypox (not much).

Why are bats responsible for so many zoonotic diseases? An episode on This Week in Virology.

A podcast episode on the life story of Joseph Lister, who pioneered antiseptic surgery, told by two comedians.

It’s estimated that vaccine mandates at US universities reduced the country’s total number of Covid deaths by 5% in autumn last year.

A major crystallography database is retracting

nearly a thousand entries of crystal structures after they were discovered to have been faked. And PLOS ONE is retracting more than a hundred papers after discovering that they went through fake or manipulated peer review.

When will we have a universal coronavirus vaccine, if ever? Hilda Bastian has a great roundup of all the research on it.

Thanks to 23andMe – it’s only a problem for me in large quantities (I have one of the less common variants that helps break down lactose), so I probably would have continued drinking dairy and feeling sick afterwards for years without realising why.

Note that milk that’s treated with lactase before it’s consumed tends to taste different (possibly sweeter due to the increased glucose content), and also tends to have a shorter shelf-life. This doesn’t affect lactase tablets, however.

A friend suggested that adult-onset lactose intolerance could be a selection adaptation to spare more scarce milk resources to children in a tribal community context. I thought that was a really interesting consideration, because it suggests natural selection at the level of community interactions, maximizing the preservation of the community's genes via its children, rather than just for maximizing any individual's own fitness.