Equations that demand beauty

The remarkable physics of constraints (author: Åsmund Folkestad)

Åsmund Folkestad is a theoretical physicist writing on aesthetics, pragmatist mysticism, and fundamental physics at Mechanics of Aesthetics. He has a PhD from MIT, produces choral electronic music and electromagnetic visual arts, and currently lives in San Francisco building AI tools for science.

Despite excelling in his single year of schooling, George Green wasn’t allowed to continue. His father instead wanted him in the bakery and—soon after—the mill. So nine-year old George didn’t have a choice. Kneading breads and grinding grain it was, for the next 27 years.

Yet, the mill-bound Nottingham boy grew up to write a masterpiece—a work that earned him a Westminster Abbey memorial and led Einstein to remark that Green had been 20 years ahead of his contemporaries.

And ahead he was. Green’s seclusion from the English men of learning gave him a strange advantage. Study of continental mathematics was actively discouraged in England at this time thanks to the rivalry between Newton and Leibniz over the discovery of calculus. The English naturally took Newton’s side and, to their detriment, cut themselves off from a Cambrian explosion of mathematics on the continent. But not Green. He exchanged mill profits for articles by Poisson, Laplace, and their like through the Nottingham Subscription Library. So, candle in hand and French on tongue, Green worked on mathematics after grinding.

Finally in 1828, at the age of 34, the miller published his paper:

Green discovered techniques to solve a type of equation that humanity was only then starting to encounter, but which we seem to find in increasingly exotic form each time we improve our theory of nature. Equations telling us not how physical systems evolve with time, but rather what systems are allowed to exist in the first place. A class that becomes more load-bearing the higher you climb, until you reach the highest known peak, quantum gravity, where this type of equation is the only one left—time itself seemingly gone. Equations that lead you to the question…

…Is it impossible for the universe not to be filled with beauty?

I.

In your introductory physics class, Newtonian particle mechanics is first on the agenda, and the quintessential question is this:

If a particle starts in this position, with that velocity, and is subject to those forces, what will its future trajectory be?

While studying this question, you get the feeling that physics is free and flexible. You get to invent all kinds of little universes. You can place particles here, you can place particles there; they can move this way, they can move that way—no one can stop you. What is not free, however, is how these things evolve as you start the clock. Only then does the problem really begin. The bishops and rooks of physics have predefined moves, but in this game you can place the pieces wherever you want before you start.

Then you get to electromagnetism, and your professor asks: what is the electric field surrounding a particle of charge Q?

Here time is nowhere to be found, beyond the fact that the question implicitly refers to a fixed moment in time. But since your professor bothers to ask, you probably cannot cook up whatever state of electric fields you want—even at a fixed instant of time. Some photographs simply cannot exist.

So which electric fields are legal? This question is answered by Gauss’ law, which is the equation Green showed how to solve.1 It is a type of equation known as a constraint equation, and this particular one restricts what electric fields are allowed to exist. It says that at any fixed moment of time, the following must be true at every point in space:

Electric charge density = divergence of electric field.

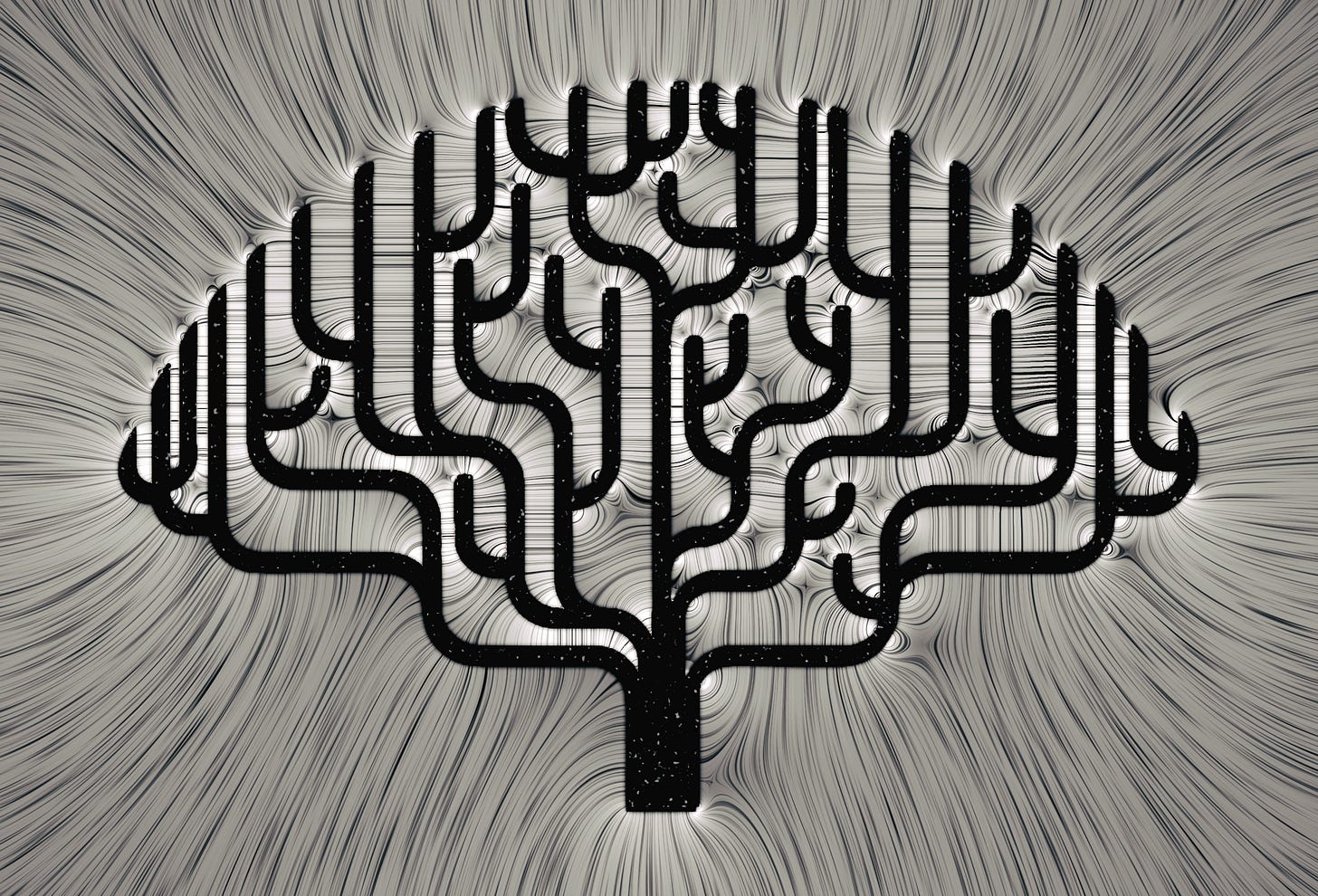

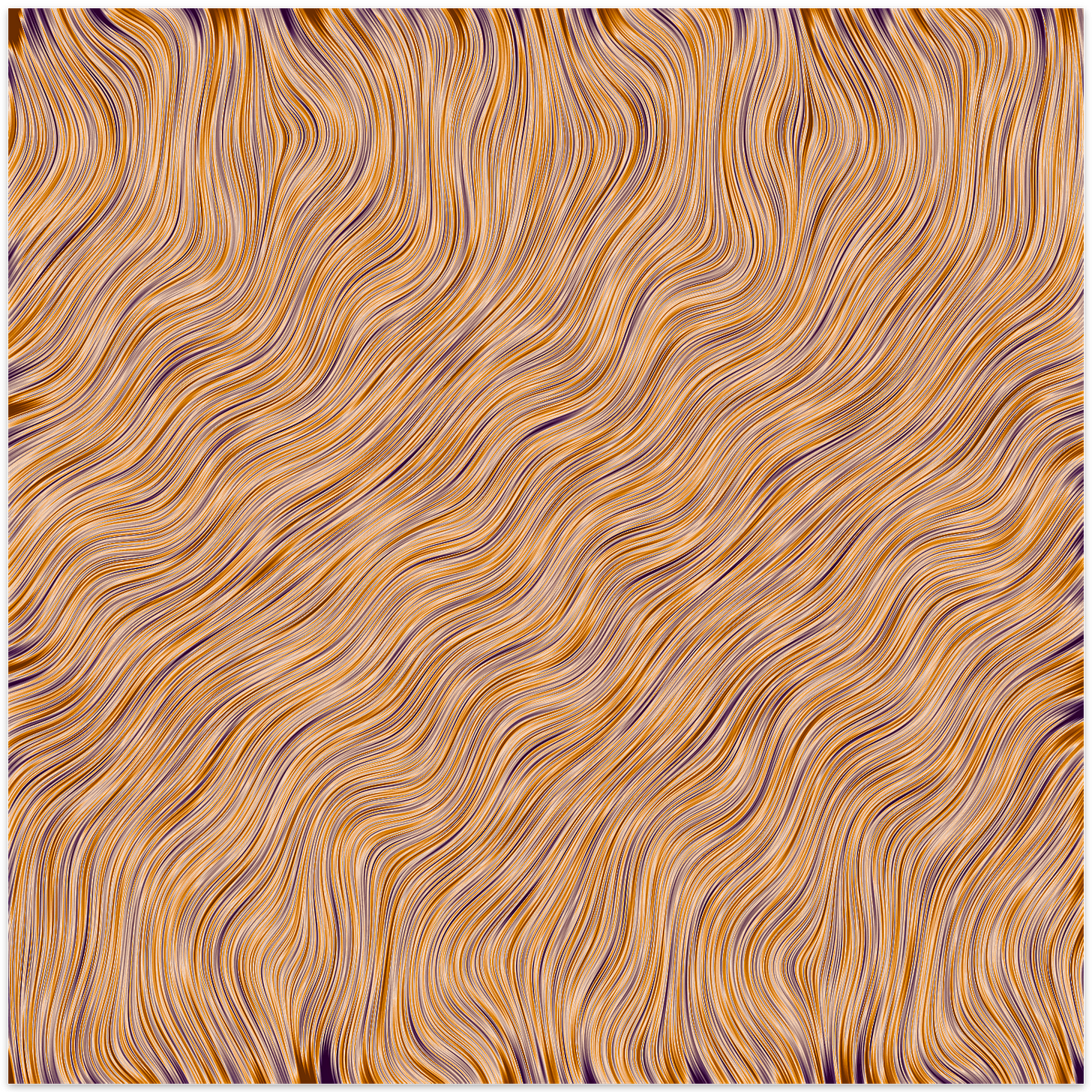

This is equivalent to saying that electric charges, like electrons and protons, act as sources and sinks for electric fields; the field is like a river, and positive charges act like springs of groundwater, while negative charges are vortices draining water down underground. And I mean this precisely. As long as we compare the electric field and the river at a frozen moment of time, the two are governed by precisely the same equation. The spatial patterns that rivers and electric fields are allowed to inhabit come from the same restricted library of possible patterns.2 Here is an electroriver I’ve simulated for the occasion:

There are no electric charges in the above simulated image, implying that the field lines always travel parallel to each other as they get close—no divergence or convergence. With electric charges present, on the other hand:

So, Gauss’ law says that electric fields are constrained. You are not at liberty to groom your corner of the universe such that the E-field swirls at random. Once you’ve spent your freedom in creating a neat decoration of electrons and protons, the electric field must respect it.

That said, the E-field is not uniquely determined either. Even after placing charges, our creator has granted us infinite freedom in how to decorate them; it just happens to be a smaller infinity than we otherwise could’ve had. This smaller infinity is bound up with the question of beauty. However, we are not prepared to understand that quite yet.

Let’s temporarily trade aesthetic satisfaction for clarity by viewing the electric field as arrows. This will also let us display the strength of the field in addition to its direction, which will pay off. So, let’s knead for a bit:

What you just saw wasn’t a time-evolution you could observe in the real world. Instead, we cycled through a family of legal snapshots of the universe at an arbitrarily chosen rate. Now, if you look at the video carefully, you see that we can’t beat down the field around the charged particle. We can reduce it on one side, but we always pay with an increase on another side. The same cannot be said further away from the charge.

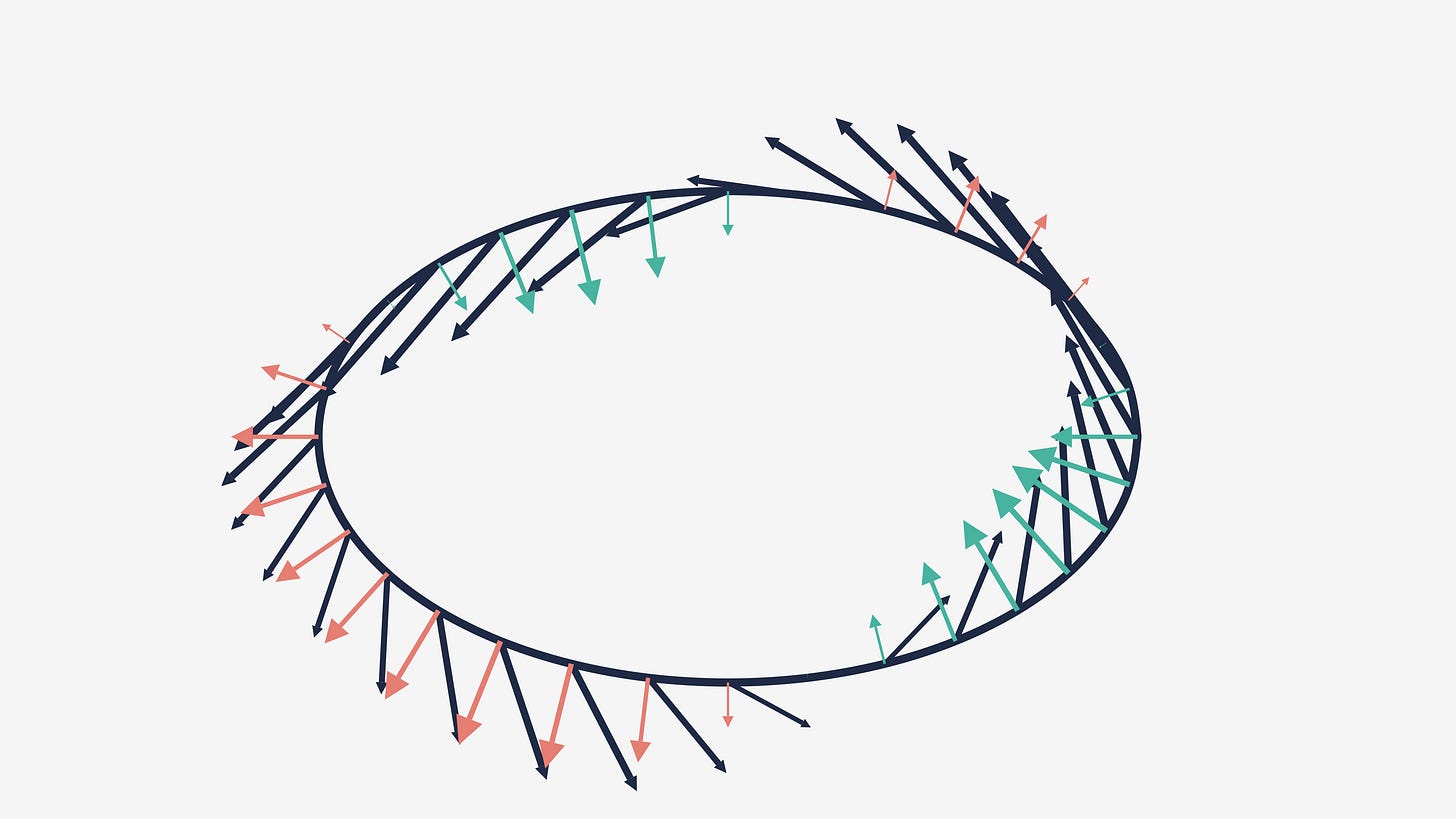

Let’s zoom in on a region far away from the charge. Next, we draw a closed surface chosen to be an ellipse for no particular reason, and focus on the field precisely on the surface itself (if you want you can pretend it’s a projection of a 3d ellipsoid to a plane):

The dark blue arrows correspond to the E-field. The coral and teal arrows represent the field projected perpendicular to the surface. If the E-field instead was the velocity field of water and you wanted to find the rate of change of water volume inside the ellipse, you’d care about the coral and teal arrows. Water grazing the surface tangentially does not contribute to inflow, no matter how fast it flows.

Now, remember that Gauss’ law is the statement that only charges act as sinks and sources. But there are no charges inside the ellipse—no “water” is being supplied or drained off. So the inflow better equal the outflow. That is, if you stack all the coral arrows on top of each other, they ought to have the exact same length as the teal ones. Let’s see it.

Let’s see what happens when we draw the ellipse around the charged particle instead:

If you look carefully, you see that the height difference between the coral and the teal stacks stays fixed in time. In fact, their difference is equal to the net charge Q of the particle inside the surface (provided you multiply each arrow by the area of the portion of the surface that it stewards—the part of the surface closer to that arrow than any other arrow).

This turns out to be a universal relationship, known as the integral form of Gauss’ law. It says that for any surface without holes, no matter its shape, if you sum up the perpendicular E-field component all over the surface (scaled by the surface area chunks), then what you get is the net charge inside it. In symbolic form, a physicist would write the following3

You now know exactly what this equation says, whether or not you have studied surface integrals (the continuous version of the discrete arrow-stacking procedure we did above). Again we can map this onto the water analogy: if water is being added or drained inside the surface, this amount must be exactly compensated by inflow or outflow.

II.

Your enemy has hoarded electrons. And for reasons I’ll never know, you’re set on tallying their total charge. Unfortunately for you, they’re in a vault.

With Gauss’ law in your pocket, however, you bypass the whole break-in ordeal. You instead scrupulously measure the electric field everywhere across the outer walls and roof of the vault (also, unfortunately, you must dig tunnels to measure underneath as well). Once done, you can sum up the field on your favorite surface enclosing the vault, and out comes the charge.4

We see here that information about charge resists localization. It always emanates into space, with the practical consequence that tallying up the charge in a region never requires you to enter it—an occasion where no cost is paid for shallowness.

Our superficiality can be used for even mightier deeds, like detecting a wormhole without the inconvenience of dying. To see this, let’s pretend that the universe has two spatial dimensions and no charged particles. Now let’s draw a 2d wormhole with electric field flowing through it:

If you draw a surface (dashed circle) around the wormhole on one side and tally up the perpendicular arrows, you clearly get a non-zero number Q. But there are no charges present. And yet, Gauss’ law says that the sum of the (arrow-scaled) length of these arrows equals the charge.

You have just discovered that wormholes mimic charged particles. It’s charge without charge. So, if God promised that the universe has no charged particles but you nevertheless measure a non-zero Gauss’ law surface sum, well, then you’ve found a wormhole. Nonzero topology of space acts just like charge.

So as you look at the wormhole from afar (bottom half in the drawing), it looks precisely like a blob of electrons. But as you travel through it (before spaghettification kills both you and time itself), you never encounter any charged particles. And the moment you turn around, it looks like a bunch of positrons are behind you! This is because the electric field arrows point either into or out of the wormhole, depending on which side you stand on, so you either tally up a charge of +Q or -Q.

Hold on, hold on. Are you sure electric charges aren’t just micro-wormholes? Is the creation of an electron-positron pair just the nucleation of a wormhole?

Charles Misner and John Wheeler also had this intuition in 1957, when they published the paper Classical physics as geometry. You now understand the core idea of that paper: matter particles might be micro-wormholes (and it suddenly feels obvious why particle and antiparticle are created in pairs). While the idea doesn’t quite work in its most naive form, it is still breathing in various exotic theories of physics, such as string theory, where charge is an aspect of the geometry of bonus dimensions that are too small to currently detect.

Whether or not you buy that, notice what just happened. By simply observing that the universe is constrained in a seemingly modest way (electric field lines don’t recede or approach each other when charge is absent), unexpected facts follow: charged particles and wormholes look the same from afar, and information about charge refuses localization in space. You might have thought that imposing constraints makes the universe impoverished, but we saw the opposite. Imposing constraints seems to fill the universe with structure. In fact, your most holy piece of music can be sculpted out of white noise.

When I’ve talked about constraints so far, I’ve implicitly talked about physical laws that belong to a class of beasts known as elliptic partial differential equations. Translation: equations that constrain how some quantity in space is allowed to behave purely based on stuff right next to it and, crucially, not in terms of anything to its past. You don’t need to know what configuration came before in time or what comes after—some rules cannot be violated. Constraint equations delineate edges in the space of possible worlds.5

Now, given the payoff we got from studying a single constraint, we ought to immediately inquire: what others exist? What do they imply?

Each time we’ve unearthed a more fundamental theory of nature, we’ve found that our constraints are just a corner of an even richer mosaic. We’ve found exotic non-linear extensions of Gauss’ law. For example, electromagnetism gets eaten by a bigger theory, where the electric field is just one face of a multifaceted dynamic object—the electroweak field—that has even richer patterns imposed on it.

If we climb all the way to quantum gravity by the most parsimonious route, which means upgrading Einstein’s gravitational equations to their quantum versions in the most vanilla way, things get weird.6 The web of constraint subsumes everything—only constraints remain! To physicists’ ongoing puzzlement, there are no time-evolution equations left.

This leads to some jazzy outcomes. We saw that Gauss’ law causes delocalization of information about net charge. In gravity, the expansiveness of the constraints seems to lead to the delocalization of all of physics! Information about everything leaks everywhere. For example, we now have the following formula for the total energy inside the surface (written in slightly impressionistic form):

With good measurements of the gravitational field/curvature of spacetime, we never have to enter a volume to know how much energy is inside it. In fact, according to our most conservative attempts at quantizing Einstein’s theory of gravity, everything that goes on inside this volume is knowable from information encoded entirely on the surface.

This means that all secrets your enemy hides in their vault can be decoded from quantum measurements (extremely complex ones) localized to a surface enclosing the vault. One dimension of space seems to be redundant. This is the idea of the holographic principle, which I worked on in my PhD, and which I’d stake real money on being true. It is almost surely the outcome of the tight constraints that gravity imposes through its quantum constraint equations.7

III.

Is the universe full of structure? I certainly hope so. I would fall into enduring despair upon learning that it was mostly featureless, or at the other extreme, full of white noise—if the universe were to have no surprise or nothing-but surprise.

The anguish I feel when contemplating a structureless universe, whether due to perfect order or maximal disorder, is a distinctly aesthetic sort of dread. This is not incidental. It takes us right to the core of what aesthetic satisfaction really is.

Namely, when you feel awe or beauty, I believe your subconscious has successfully come up with a valid abstraction. Your brain has, relying on its impressive array of experience and sensory processing capabilities, discovered symmetry and redundancy in the incoming sensory stream. It has found an underlying generating mechanism that enables partial in-advance prediction of incoming sensory data, letting it validate the correctness of its abstraction without any room for cheating. It has found verifiable structure.

Structure resides in the borderlands between order and disorder. It’s present when something is neither as simple nor as complex as it otherwise could’ve been. It arises in that zone where, if you look hard enough—but only then—you will be rewarded. At absolute order, there is nothing left to predict, while at total disorder, prediction is doomed to fail.

In possession of a new abstraction, your brain is now more likely to predict future sensory signals. This is useful for survival, and so evolution rewarding us upon discovery of abstraction feels almost obviously true, once you think of it. The savannah man enjoying the discovery of subtle distinctions in color avoids poisonous berries, while his fascination with intricate cloud motion lets him bring the family to the caves before the storm.

So, must the universe be filled with beauty?

Could it be that the universe is low on structure and new things for us to abstract? You might say no—have we not seen that it is rich with it, given its crystal lattices and human civilizations? These certainly give lower bounds on the amount of awe to be had, but oh, how little we have seen across space, time, and even further beyond—where those concepts stop making sense.

An artist conceiving a masterpiece has three routes to structure: additive, subtractive, and transformative. The additive route is taken by the painter filling a blank canvas, while the subtractive path is taken by the electronic musician carving timbres out of noise samples. The collage artist takes the transformative path, shuffling complexity that is already there.

What about the universe itself? We could try to carefully study the laws that govern its unfolding with time—the additive or transformative route. At an empirical level, as far as our eyes and telescopes see, the universe is in the process of birthing incredible structure. It moves in ways that let electrons, protons, and photons grow into The Well-Tempered Clavier.

Yet, at the theoretical level, I don’t know of any assurances that the universe will keep adding structure, and a fat entropic cloud hangs above: the second law of thermodynamics—the statement that the universe will forever get more surprising.

The growth of surprise is good if we start with something simple and predictable. Remember, structure lies between total simplicity and disorder. So the second law lets featureless worlds climb towards structure, for a while. At some point, however, the curve starts going down—more surprise means the fragmentation of structure, rather than growth. There are increasingly many things to predict, but the probability of success in doing so goes down even faster, and what’s left to predict would not be recognizable as worth the effort: functionally infinite mixes of micro-patterns with no unifying principle.

And so, the heat-dying universe stares at us.

I’m not confident that heat death will come to pass, however. True, it seems likely if you accept the current working model of the universe as the end of the story and also forget about quantum effects, holography, and and other looming uncertainties. In extrapolating to extreme scenarios such as the heat death of the universe, I’d not bet much that we can ignore those. As just one example, strange and hard-to-understand things happen when you try to apply holography to cosmological scales, and it is clear that the top experts are confused, although the research is quite active at the moment (see for example this Quanta Magazine article with interviews with several former colleagues).

And so, leaving behind a thicket of question marks that I’ve only vaguely alluded to, and which are not easy for us to untangle here, what other principles do we have to help us?

Constraint equations, of course. While humanity hasn’t found even a single law we’re confident is universally valid, the constraint equations that come with electromagnetism, gravity, and the nuclear forces are as universal as they seem to get. They appear to constrain every possible state in the regime of physics we remotely understand. All blocks of possibility are chiseled down, forbidding the anarchy of white noise, birthing patterns for us to stumble upon.

Beyond our horizons of knowledge, how many more of them exist? Do sublime oceans of structure lie outside the utterly negligible fraction of the matter in the universe we understand well? A fraction that appears to be at the very most

0.000000000000000000000000000000001%.

The second law of thermodynamics pushes the universe towards disorder, but if constraint equations run as deep as they seem, they might still make it impossible for the universe not to be filled with beauty.

Further Reading

“A Natural History of Beauty” by Kevin Simler

“Great scientists follow intuition and beauty, not rationality” by Erik Hoel

Technically speaking, Green showed how to solve a special case, where Gauss’ law reduces to what’s called the Poisson equation. But the hard part of solving Gauss’ law is the contribution that comes from the Poisson equation. Also, Green’s method, now referred to as the method of Green’s functions, work for a much broader class of problem.

When I mean the “spatial pattern” of the river, I mean its velocity field profile, given by the velocity vector field. Also, being allowed to take the same set of legal patterns does not mean that their statistical distribution is the same out in the world. It is most certainly not.

Like the man of refinement I aspire to be, I keep my volume forms implicit and set the vacuum permittivity to unity.

Be aware though. If your enemy is clever, they have collected a bunch of positrons in the vault to throw you off.

This is not correct at the technical level—rather, constraint equations constrain us to live on certain sub-manifolds (and sometimes not even proper manifolds, in the case of gravity).

You might wonder how I can say any of this, given the usual lore about how quantum gravity is the biggest unsolved mystery in physics. Well, that is only partially true. First, we do know how to straightforwardly upgrade Einstein’s equations to a quantum theory at low energies. We haven’t measured the predictions of this theory because the effects are so feeble, but taking this theory to be correct at low energies is the most parsimonious thing to do. Second, while the theory’s predictions start blowing up at high energies, there are certain structural properties that seem highly natural, universal, and independent of how the theory breaks down. Sometimes positing that those survive in the final theory give a lot of mileage. Additionally, speculative well defined theories like string theory might also succeed at defining _a_ quantum gravity theory (who knows if its the right one) that shares these properties, giving a proof of principles.

And it is likely true independently of whether or not string theory is true, even though the principle was discovered in the string theory contQext. Look at arXiv 0808.2842 and also later work 2107.14802 and refs/citations from there for very general arguments with parsimonious assumptions.

The most beautiful equation was discovered by Aczél, it's his 1966 Characterisation theorem for bounded systems.

Overlooked by all, including Aczél.

It's the theorem that gives Einstein his velocity addition.

Light is bounded, because it exists in a bounded universe.

Euclidean space is imaginative, nit real, because in reality, nothing blows up because everything is bounded, associative per Aczél.

Facts