The game theory of strategic ambiguity explained with Seinfeld

Author: Lionel Page

Lionel Page (@lionelpage) is a Professor of Economics and the Director of the Centre for the Unification of Behavioural and Economic Sciences at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Optimally Irrational and discusses on his eponymous Substack how insights from economics, psychology, and other behavioural sciences help make sense of the often puzzling aspects of human behaviour.

One of the seemingly strange aspects of human communication is that we often do not express what we think explicitly, and directly, but in implicit, indirect, and veiled ways using vague statements, hints, and innuendos. This may seem to defeat the purpose of communication. Why not communicate as clearly as possible if communication is to say something?

This question opens the door to fascinating insights into how everyday communication works and why it works the way it does. In this post, I’ll discuss how our use of ambiguity makes sense once we understand the strategic interactions behind our verbal exchanges.

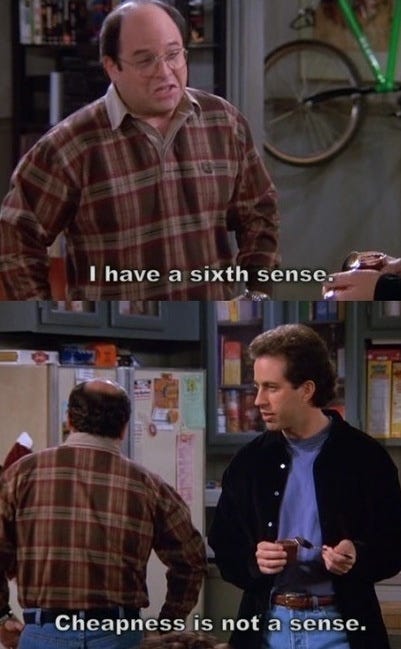

To illustrate these ideas, I’ll use scenes from the 90s sitcom Seinfeld, self-described as a “show about nothing”, where four New Yorkers over-analyse what happens in their daily lives. The show is clever, funny and insightful. It is a trove of resources to discuss the strategic layers behind everyday interactions.

Cooperation and conflicts in communication

Communicating, and exchanging information is fundamentally cooperative. I have previously discussed how principles of cooperation shape not just what people say but how people communicate, thanks to a shared understanding that they want to be understood.

However, communication interactions are not pure cooperative games. They are what game theorist Thomas Schelling (1960) called mixed-motive games featuring both cooperation and conflict. We do not always agree with the people we talk to because we have different views (goals, preferences and beliefs). Finding out each other’s views and whether they are compatible is what Schelling calls the identification problem:

Identification, like communication, is not necessarily reciprocal; and the act of self-identification may sometimes be reversible and sometimes not. One may achieve more identification than he bargained for, once he declares his interest in an object. - Schelling (1960)

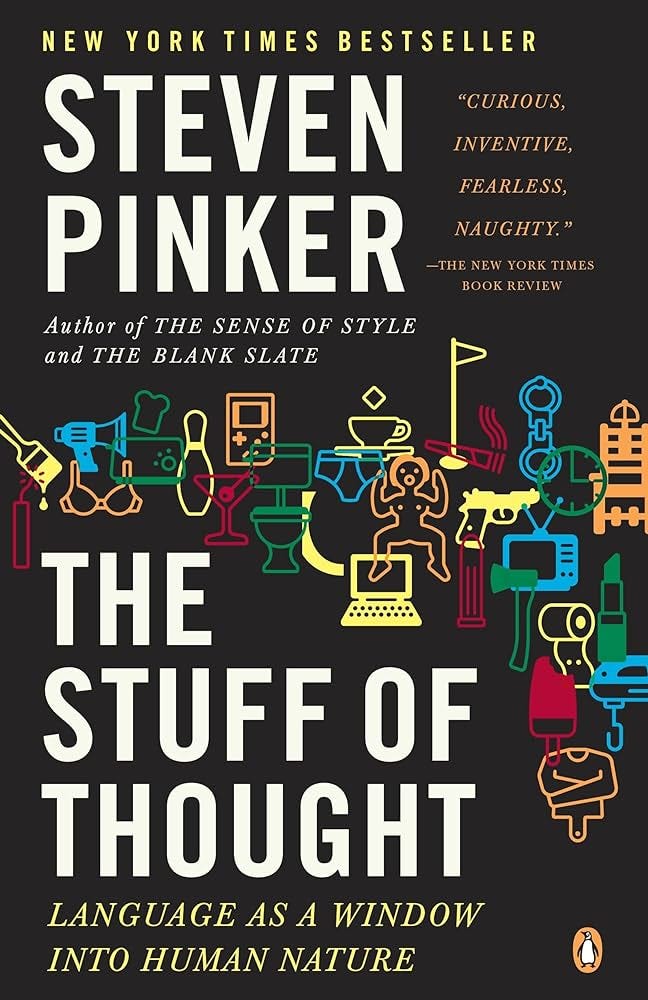

A speaker can achieve “more identification than he bargained for” when he has clearly identified his views and they happen not to be shared by the listener. As Stephen Pinker points out in his book The Stuff of Thought (2007), this possible conflict helps explain the role of cultivated ambiguity in our discussions. Ambiguity allows speakers to strategically navigate uncertainties about their respective views.1 They can, for instance, use indirect speech—using context to indirectly convey meaning—to avoid being too explicit.

As long as speakers do not explicitly identify their views, people engage in mind reading, forming higher-order beliefs (beliefs about others’ beliefs).2 Once somebody states their views explicitly, it becomes common knowledge: the speaker’s and the listener’s higher-order beliefs become fully aligned. They both know the views of the speaker, they both know that they know them, they both know that they know they know them, and so on. If these views are not shared by the listener, they can’t be taken back. They are out there.

Common knowledge of differences in preferences and beliefs can be risky. This is why ambiguous statements, hints and innuendos are often used to convey meaning while avoiding common knowledge and retaining plausible deniability, if needed. When Bob makes an ambiguous statement about his views, Alice is likely to understand. However, if she does not share the same views, Bob may pretend he did not say anything special (fake first-order belief), he may pretend not to be aware that Alice understood what he meant (fake second-order belief), or he may seem oblivious to the fact that Alice understands he knows that she understood his statement (fake third-order belief).

Comic effects

The use of ambiguous statements is a great source of comedic situations in popular comedies.

Misunderstandings

As discussed by behavioural economist Georg Weizsäcker in Misunderstandings (2023), failures to understand each other arise from false higher-order beliefs when engaging in mind reading.3 For instance, Alice may think Bob does not want to go out because she wrongly believes he thinks it will rain (false second-order belief). Bob may believe Alice does not want to go out to be unpleasant, since she must know he thinks the weather will be great for an outing (false third-order belief).

Ambiguous statements, hints and innuendos are routinely used for comic effects to induce misunderstanding where the veiled meaning is lost to some, and the fact that this meaning is lost is also sometimes lost to the speaker leading to miscoordinations, and awkward moments.

Fake pretence

Indirect speech generates layers of meaning not explicitly present in the discussion. The disjunction between what is said and what is meant is also used for comic effect. A good example is when people exchange overly polite niceties, while actually fiercely disagreeing.

The speakers’ fake pretence that their interaction adheres to the literal meaning of what they say (e.g. the polite niceties) creates tension. Over time, joint awareness of the actual meaning grows as the speakers’ higher-order beliefs align: Bob knows Alice’s niceties are only a facade; Alice knows that Bob knows that; Bob knows that Alice knows that he knows, and so on. As this joint awareness grows, the speakers get closer to common knowledge. The persistence of fake pretence becomes growingly vain until the residual uncertainty is so small that people drop all pretence in a “masks off” moment.4

Negotiating partnerships

Dating and negotiating romantic partnerships

A typical identification problem is finding whether someone wants to be our romantic partner. It is not an easy problem to solve as our social interactions are fraught with asymmetric romantic interests. This Seinfeld interaction highlights the danger of being too explicit. George suggests candidly revealing strong feelings to his new girlfriend.

GEORGE: I might tell her that I love her. I came this close last night, then I

just chickened out.

JERRY: Well, that's a big move, Georgie boy. Are you confident in the 'I love

you' return?

GEORGE: Fifty-fifty.

JERRY: Cause if you don't get that return, that's a pretty big matzoh ball

hanging out there.

The “matzoh ball hanging out there” is awkwardness, the feeling experienced when there is common knowledge of different relationship preferences. Ambiguous overtures are therefore a feature of such situations. They offer the opportunity for the other person to reciprocate while offering cover if the intention is not reciprocated. In that latter case, people can pretend that no overture was made.

Ambiguous overtures create comic opportunities as they may be misunderstood if taken literally. In one situation, George is invited at midnight to “come upstairs for some coffee” by his date. He declines, saying it is too late for coffee.

As the woman leaves, visibly disappointed, George realises the meaning of that invitation and is mortified. Later he unpacks what happened with Jerry and Elaine:

GEORGE: She invites me up at twelve o clock at night, for coffee. And I don't go up. "No thank you, I don't want coffee, it keeps me up. Too late for me to drink coffee." I said this to her. People this stupid shouldn't be allowed to live. I can't imagine what she must think of me.

JERRY: She thinks you're a guy that doesn't like coffee.

GEORGE: She invited me up. Coffee's not coffee, coffee is sex.

ELAINE: Maybe coffee was coffee.

GEORGE: Coffee's coffee in the morning, it's not coffee at twelve o clock at night.

Bribery

Human interactions are characterised by cooperation regulated by social norms. These norms often take the form of impersonal rules applying equally to all members of society. However, human cooperation can also take the form of direct reciprocity in small networks of friends and family members.5 This type of cooperation can conflict with impartial rules, like when one preferentially hires one’s friend or family member for a position (favouritism, nepotism). One such conflict is when interpersonal favours are exchanged to bypass impersonal rules. This practice is labelled as bribery in societies with strong rule of law.

The identification problem for a would-be briber is ascertaining if a rule-enforcer is amenable to being bribed. Bribe offers are typically implicit to avoid the unpleasant situation of offering a rule-breaking bribe to an unwavering enforcer. In The Stuff of Thought, Steven Pinker uses these aspects of bribing attempts to explain the anxious feelings when trying to convince a maître d', to jump a queue for a small payment. People avoid being explicit and, instead, use indirect speech like “it would be great if something could be done”. It is exactly what Elaine attempts when trying to get a table earlier at a Chinese restaurant:

ELAINE: Boy, we are REALLY anxious to sit down.

BRUCE: Very good specials tonight.

(Elaine puts the bill on the open reservations book)

ELAINE: If there's anything you can do to get us a table we'd really appreciate it.

(Bruce fails to get the hint after further exchanges)

ELAINE (Gives him the money): Here, take this. I'm starving. Take it! Take it!

(Bruce shrugs and takes it)

BRUCE: Dennison, 4! (goes over to 4 ladies) Your table is ready.

ELAINE: No no, no, I want that table. I want that table! Oh, come on, did you see that? What was that? He took the money, he didn't give us a table.

Because the statement is not explicit, its meaning is missed by the maître d' who takes the money but does not let them jump the queue.

Political positions

Another identification problem arises from possible differences in political opinions. Two people who ignore their personal views will only unveil them progressively to avoid the awkwardness of realising their positions are at odds. In a classic article on the games we play hiding and revealing our views in our verbal exchanges, the economist

(1994) describes the dynamics between two individuals who do not know each other well:

Each speaker, seeking recognition and reinforcement, looks for the positive feedback which encourages that candor in discussion possible only among the like-minded. The dialogue may evolve into an intense and intimate exchange, or it may lapse into vague and meaningless banter, depending on what the speakers are able to learn about one another. If real communication eventually occurs, the path to it will have been paved by overtures of calculated imprecision. - Loury (1994)

An illustration is Elaine wanting to ascertain if her boyfriend is pro-choice, like her. One option is to ask him directly, but as she states in another episode “if I ask him, then it's like I really want to know”.6 Explicit questions signal an interest that may suggest our own positions. Inquiring about others’ political positions is therefore often made indirectly by dropping a hint or broaching a topic, paving the way for the other person to provide some of their views before continuing.

Elaine chooses to incidentally mention a fictitious story about a “friend”:

ELAINE: Recently I've been thinking about this friend of mine.

CARL: What friend?

ELAINE: Oh, just this woman...she got impregnated by her troglodytic half-brother, and decided to have an abortion. <Waits in suspense for what Carl's response will be.>

CARL: You know, someday...we're going to get enough people in the Supreme Court to change that law.

<Elaine breaks down in tears.>

Turning down partnerships with tact

When you wish to turn down a request or end a partnership, it may be beneficial to avoid explicitly discussing the reasons. Staying ambiguous may prevent the reasons from becoming common knowledge, leading to bad blood in future interactions. Hence romantic relationships end with “it is not you, it is me” and applications are rejected with “this decision doesn’t reflect the quality of your application”.

When George fails to grasp the meaning of a polite firing notification, he gets its untold motive stated explicitly.

THOMASSOULO: George, I’ve realized we’ve signed a one-year contract with you, but at this point I think it’s best that we both go our separate ways.

GEORGE: I don’t understand.

THOMASSOULO: We don’t like you. We want you to leave.

Making requests

Politeness

Making requests is another situation where conflicts can arise. A request potentially says something about expectations of mutual respect and duties in a relationship. Alice may wish Bob to do something for her, but asking explicitly may unveil mismatches in expectations. An explicit request may suggest Alice expects Bob to accept. Bob may feel pressure to comply or guilt if he doesn’t. If Bob feels the request goes beyond what Alice is entitled to expect, he may resent it, whether he complies or not.

Here again, indirect speech can be a solution. “If you could close the window, that would be great” is, at face value, a comment about a counterfactual possibility, not an explicit request. It is less likely to offend Bob if he has different views about what expectations Alice should have towards his duties to her. Whether Alice’s request is denied or not, it is less likely to generate awkward feelings about mismatches in mutual expectations than if an explicit request was made.

Indirect speech can however make it unclear that a request is a request. And because requests can be unclear, people may perceive a request when there was none. It requires mind-reading to understand if a statement is an implicit request or not. It is another source of comic situations like when Elaine assumes a request is made for her to babysit. She answers positively, only to learn she is not even considered a worthy potential babysitter.

VIVIAN: I'm gonna need someone to look after him tomorrow evening.

ELAINE: Tomorrow evening, sure.

VIVIAN: Do you know anyone responsible?

ELAINE: Do I know anyone??

VIVIAN: Well, if you think of anybody, give me a call.

Veiled threats

Threats are another type of request, using the prospect of sanctions or violence, to compel acceptance. However, sanctions and violence often break social rules. Making them explicit risks being held accountable later. A veiled threat conveys the message of the threat while maintaining plausible deniability. Steven Pinker gives the classic example of a mafioso offering “protection” to a shop owner: “Nice store you got there. Would be a real shame if something happened to it.” It may be harder to report that man to the police, even though the implied meaning is clear.

Seinfeld offers another example when Kramer, campaigning against junk mail, is abducted by the US Mail. The postmaster general, while holding Kramer captive, pronounces ominously “Now, you want that mail, don't you Mr. Kramer?” The tone and setting convey the threat, getting Kramer to drop his protest.

POSTMASTER GENERAL: Maybe you can understand why I get a little irritated when someone calls me away from my golf.

KRAMER: I'm very, very sorry.

POSTMASTER GENERAL: Sure, you're sorry. I think we got a stack of mail out at the desk that belongs to you. Now, you want that mail, don't you Mr. Kramer?

KRAMER: Sure do!

POSTMASTER GENERAL: Now, that's better.

Sanctions

As stated above, cooperation is key to our social interactions and social norms regulate our cooperation. When norms are infringed, social sanctions ensue. However, as Binmore (2005) points out, sanctions do not need to be explicit:

Nearly all punishments are administered without either the punishers or the victim being aware that a punishment has taken place. No stick is commonly flourished. What happens most of the time is that the carrot is withdrawn a tiny bit. Shoulders are turned slightly away. Greetings are imperceptibly gruffer. Eyes wander elsewhere. These are all warnings that your body ignores at its peril. - Binmore (2005)

These are the first signs that you may be dropped as a valuable social partner.

Sarcastic jokes

Sarcastic jokes are such a sign. They may indicate disapproval but, wrapped in a seemingly humorous statement, they avoid common knowledge of the extent of disapproval. Sarcastic jokes and snide remarks are a common feature in the show.

Passive aggressiveness

Signals of implicit disapproval masked behind apparently normal interactions are gathered under the concept of passive aggressiveness. It can take the form of non-verbal behaviour suggesting a negative thought behind a literal verbal exchange. In one Seinfeld scene, a man clears his throat when describing the death of George’s fiancée as an accident, seemingly undermining this description.

WYCK: Well, you should choose the poem since you knew Susan best at the time of her unfortunate <clears his throat>...accident.

[…]

GEORGE: Jerry, a throat-clear is a non-verbal implication of doubt - he thinks I killed Susan!

Passive aggressive behaviour offers two pathways for comic effect. One is for people to maintain a contrived fake pretence that no ill-meaning is meant while engaging in repeated passive-aggressive exchanges. The other is for the aggressor’s meaning to be called out, with that person trying to keep the fake pretence that nothing ill-intended was meant. This is illustrated when Elaine implicitly accuses Jerry of encouraging her recovering alcoholic boyfriend to drink.

ELAINE: You knew he was an alcoholic. Why'd you put the drink down at all?

JERRY: What are you saying?

ELAINE: I'm not saying anything.

JERRY: You're saying something.

ELAINE: What could I be saying?

JERRY: Well you're not saying nothing you must be saying something.

ELAINE: If I was saying something I would have said it.

JERRY: Well why don't you say it?

ELAINE: I said it.

JERRY: What did you say?

ELAINE: Nothing. It's exhausting being with you.

Elaine is exhibiting bad faith. She did mean to imply something but did not want to “say” it explicitly.

The presence of both conflict and cooperation in our interactions explains the rich, complex texture of our exchanges. We often do not convey information plainly because there is more to gain by conveying it implicitly, while preserving enough uncertainty to renegotiate the interpretation of our statements in later interactions. This is another aspect of the rich layers of strategic interactions behind our everyday conversations.

References

Binmore, K., 2005. Natural justice. Oxford University Press.

Fukuyama, F., 2011. The origins of political order: From prehuman times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Goffman, E., 1956. The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY, 259.

Loury, G.C., 1994. Self-censorship in public discourse: A theory of “political correctness” and related phenomena. Rationality and Society, 6(4), pp.428-461.

Pinker, S., 2007. The stuff of thought: Language as a window into human nature. Penguin.

Pinker, S.. 2007. The evolutionary social psychology of off-record indirect speech acts. Intercultural Pragmatics 4(4): 437–461.

Raihani, N., 2021. The social instinct: how cooperation shaped the world. Random House.

Schelling, T.C., 1960. The Strategy of Conflict. Harvard University Press.

Weizsäcker, G., 2023. Misunderstandings: False Beliefs in Communication. Open Book Publishers.

He also develops this further in his article “The evolutionary social psychology of off-record indirect speech acts”.

If we call a belief about the world a first-order belief (“I believe that it is going to rain”) a second-order belief is a belief about somebody’s belief (“I believe that Jane believes it is going to rain”), and a third-order belief is a belief about a second order belief (“I believe that Jane believes I believe it is going to rain”).

You can check out his Substack Researching Misunderstandings.

This dynamic is precisely described by Erving Goffman in his classic book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956) when discussing tact—the fact of pretending to take at face value others’ claims about what’s happening in the interaction. Here is how he describes it (I insert the corresponding orders of beliefs in italics):

Whenever the audience exercises tact, the possibility will arise that the performers will learn they are being tactfully protected. [Second order belief: The speaker knows that others know there is a discrepancy between what is claimed to be happening/said and what is actually happening/said.]

When this occurs, the further possibility arises that the audience will learn that the performers know they are being tactfully protected. [Third order belief: the listener knows that the speaker knows they know.]

And then, in turn, it becomes possible for the performers to learn that the audience knows that the performers know they are being protected. [Fourth order belief: the speaker knows about the listener’s third-order belief.]

Now, when such states of information exist, a moment in the performance may come when the separateness of the teams will break down and be momentarily replaced by a communion of glances through which each team openly admits to the other its state of information. [Common knowledge is reached in a masks-off moment.]

At such moments, the whole dramaturgical structure of social interaction is suddenly and poignantly laid bare, and the line separating the teams momentarily disappears. Whether this close view of things brings shame or laughter, the teams are likely to draw rapidly back into their appointed characters. - Goffman (1956)

This is what Francis Fukuyama (2010) calls patrimonialism.

This statement is made as Elaine is unsure about her boyfriend’s racial background. She is curious about it but does want to be seen as caring about it.